Fun with TCP CUBIC

My work flow has mostly involved taking measurements to make sure that the problem I'm trying to solve is indeed a problem, trying to reason about the resulting measurements in terms of protocol behaviour/interleaving, and exploring what I can do to improve these measurements in a manner that is practical. As part of the work however, I needed some baseline measurements for TCP behaviour so that at the end of my thesis, I can say something like, "See? After what I did, we now have MOAR TCP AWESUM!!111"

Of course, TCP and wireless are two things that don't really get along well. TCP sees packet loss and delays as "congestion", and depending on the congestion avoidance algorithm, will back down upon hitting such a situation. However, wireless networks suck (and will continue to suck). You can make it suck less probably, but it'll always stay above the suck-thresh. Interference in the physical channel will always be there (like memories of The Phantom Menace, which will haunt us forever). Furthermore, if there's another station on the same channel communicating over a lower bit rate, your station's performance can be degraded real bad (known as the 802.11 performance anomaly). This means that Murphy in the physical layer (only your first hop in most cases!), can end up causing TCP to believe that there is congestion at any of the many links that lead to the destination, and actually back down.

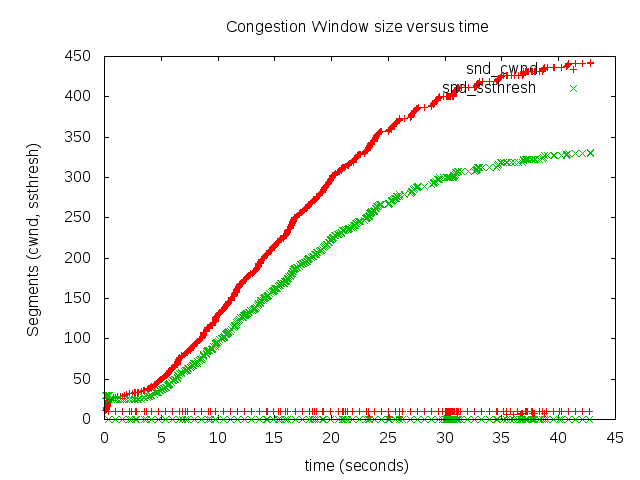

Linux uses TCP CUBIC as the default congestion control algorithm since kernel version 2.6.19. Without going into details of how the different TCP thresholds work in CUBIC, let's look at how its congestion window (CWND) curve looks like.

The above is a measurement of the CWND size on a per packet basis, for a flow generated using iperf. The test network comprised of my laptop running the iperf client with an access point one hop away, bridging all traffic to a server behind it via a switched LAN. I'm sharing a wireless channel with a whole bunch of other nodes. The red line is the CWND size, and the green line is the slow-start threshold (ssthresh) value. As for some quick TCP background, the red line indicates how many bytes TCP is willing to keep outstanding, and the green line indicates the threshold at which TCP says, "Ok, I think I should not get too greedy now, and will back-out if I feel the network is congested".

The graph above is a typical TCP CUBIC graph. When the congestion window (red) is less than the ssthresh value (green), the CWND increases in a concave manner (really fast). This can be seen by the near vertical spikes around seconds 3, 9, 35, and 37. When the CWND value is higher than the ssthresh value, TCP CUBIC plays safe, and tries to increase very slowly. For instance, look at how slowly the stretch between 22 and 30 is growing.

As you can see, TCP is detecting congestion multiple times, thanks to a noisy channel, and adjusts itself accordingly.

Next, we look at the curve in a channel where there is no contention at all (that is, no else on the channel except my wireless interface, and the access point I'm talking to).

Clearly there is no congestion here. The CWND value crosses the slow-start threshold very early (around the 1st second), plateaus since that point, and then goes convex around the 5th second. It then keeps probing for more bandwidth, finds it, and increases the window size steadily over time.

Comments